The Mars Society is conducting an ambitious two-phase Mars 160 Twin Desert-Arctic Analog mission to study how seven crewmembers could live, work and perform science on a true mission to Mars. Mars 160 crewmember Annalea Beattie is chronicling the mission, which will spend 80 days at the Mars Desert Research Station in southern Utah desert before venturing far north to Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station on Devon Island, Canada in summer 2017. Here’s her fourth dispatch from the mission:

None of us have traveled to Mars, and we don’t really know what it will be like. The challenges for humans in long-duration space travel have yet to be experienced.

Here at the Mars Desert Research Station, we are seven for the first phase of our Mars 160 science mission. We are living in simulation in a Mars analogue in a remote desert where temperatures can range from 14 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 10 degrees Celsius) in winter to more than 104 degrees F (40 degrees C) in summer. [See more Mars 160 photos here, and get daily images by the Mars 160 crew]

When it comes to understanding how life might be in an enclosed community in an extreme environment off Earth, unless I move to Eigg (an island off the west Scottish coast), this is about as close as it gets to living in a small frontier microsociety on Mars.

This evening, after a ruckus in our crew family about report writing (I won’t go into it), in my loft I was thinking about crew morale and how we manage to stay healthy, as well as work hard and live together in such a small container in an enormous desert. I found something on my laptop that I wrote a while ago that started me thinking. This is what I wrote:

“When we leave the security of home and the warmth of our fires to travel to other planets as explorers or even as refugees on starships, we will be constantly challenged by our new circumstances. We may be menaced by those who control our oxygen. It’s possible that we could end up living as spectators to our own imprisonment, trying to exist amongst people who are aggressive or broken. On Mars, as we contend with the threat of real danger, pain or harm, anxiety and the continual tension in shared space could lead to deteriorating morale, to stagnation or depression, to a loss of well-being in management terms, and for us, damage to human health.” (Editor’s note: This passage is part of a piece Beattie wrote called “Art and Change in Extraterrestrial Societies.” It appeared in the book “Dissent, Revolution and Liberty Beyond Earth,” which was published by Springer in 2016.)

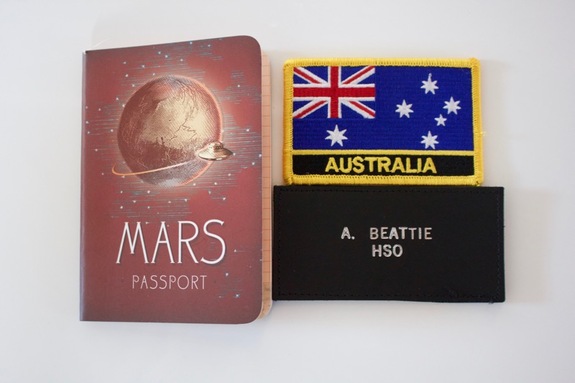

Our human health. Although I’m an artist and my own research tests out the value of geological field drawing in a spacesuit, my role on this crew is also as Health and Safety Officer (HSO on the spacesuit badge).

Credit: The Mars Society

Even though I have the Mars passport, we are not travelling on a one-way ticket to Mars. In terms of safety, it’s clear to us we should follow the rules of the mission and the regulations of the Mars Desert Research Station, as these protect us. Our health relates directly to the different kinds of activities we do every day. If we are not healthy or safe, we can’t do our work.

In the outside world, there is often a clear demarcation between working time and leisure time. Here things are not so simple, as in fact we are working most of the time. The average working day for any crewmember on this mission is between 11 and 12 hours, not counting food preparation. [Buzz Aldrin: How To Get Your Ass To Mars (Video)]

And on a mission of 30 days to date, we have had two scheduled leisure days off. (Most of the crew chose to work at least part of these days off.) What happens is, we go outside and work, and then we come inside and work again! I think you get the idea. There are requirements for the mission, and we really are a productive crew.

On an average working day at the Mars Desert Research Station, what are we actually doing, and, most importantly, how does our busy working life impact upon our health?

As in a normal household, there are many things that need to be done on a daily basis, to ensure we live well and stay within our limits. Our day can be extraordinary if you are out on a field trip, but in terms of hab routine, it’s groundhog day.

We are quiet getting out of bed around 7 in the morning. Coffee is on and someone is cooking. We eat together, do dishes in rotation then meet for the day’s briefing. Dr. Alexandre Mangeot, our commander, runs through the tasks and commitments for the day, then he takes notes while each of us identifies daily goals and scopes them out in the time available. We plot out all of our day, nominating work spaces, meetings with others and the resources we need, including requests for access to the internet. We delegate daily report writing as well as cooking and cleaning. Then we discuss science goals and reiterate roles for the EVA (extravehicular activity) of that day.

After our briefing, we disband to different jobs for EVA prep. Downstairs, crewmembers leaving for field science dress in preparation while others check equipment. Our engineers confirm communication gear, batteries, fuel and so on. We all assist to help the EVA crew suit up and depart. Someone always has the responsibility of communicating with the away team (HabCom for the EVA crew).

Then those who are left at the hab begin their work. This is different for each of us. On our crew, science generalists like myself are cross-trained to work with scientists. Today Anushree, our crew biologist, and I continue our study of the physical ecology of the hypoliths (specifically chasmoliths and endoliths) in the analog environment of the Utah desert. This took several hours. Yusuke practiced spot tests on lichens while Alex mopped the floor and cooked lunch. The rest of our crew returned from the EVA with lichen samples and we ate. Lunch time is when we really stop and talk.

Credit: The Mars Society

After lunch, Alex spent an hour working on the technology for his spacesuit project, Claude-Michel pumped water, and then fixed the 3D printer, while the rest of us worked on writing up their research or daily reports for the evening’s Mission Support. (Here we go: We need to send five reports — a mix of the Science Report, the EVA Narrative, the Journalist Report, the Food Report, the Engineering Report, the Photo Report, Phrase of the Day and Sol Diary.) The purpose of some reports is for publication on our website as outreach, and some communicate our status with Mission Support, like the Engineering Report. We also might have requests for assistance and information from CapCom. Today, my request to our Mission Support will be about how to correctly treat a scorpion sting. (We found a scorpion downstairs; no one was bitten).

At 3 p.m. we meet at the kitchen table to do a round of psychological testing for the Russian Institute of Biomedical Problems. (This was group problem solving.) At 4:00, Jon Clarke and I discussed the data we’ve collected in terms of any preliminary findings for the EVA project, which looks at the science operations for our mission. We talked and wrote copious notes. Anastasiya made a loaf of bread for breakfast. Yusuke finished his article for National Geographic Japan. Alex and Claude-Michel started the 3D printer and printed a test run. Anu finished a science report on lichens. Jon had a shower. We only have one shower a week, so every day is special for someone. I am waiting for Sunday; my hair is filthy.

At 5:00, we did yoga and body strength training for an hour while others cooked and continued to write their reports. Yoga is fantastic; I love it. We have also set up a hanging bar and ropes that I want to learn to climb. After dinner we cleaned up and met for the debrief, where we discussed what has been done today and what else needs to happen that didn’t. At 7:00, CapCom, our Mission Support, opens. By that time, we are ready to battle our slow and challenging internet to send in queries and daily reports to Mission Support. It always takes much more than an hour to send files, even though we have most of them uploaded and ready to go. There can only be one person on the internet at a time, and we save the data for CapCom by switching off the internet during the day. CapCom closes its doors at 9 p.m., and by this time, most of us are back to working on individual projects. This goes on until bed at 10. Once a week we watch an episode of “The Expanse.” Often those who have been out in the field go to bed early because they are so physically exhausted.

If you managed to stay with me during that description of our ordinary day and you have not dropped off to sleep yourself, you are doing well. You can see we thrive on routine.

Now, we are about a third of the way through our mission here at MDRS, and the crew has actually been keeping records of what kinds of activities they do every day. Here’s some data from Jon Clarke’s diary of daily activity. Pinch yourself now if you are feeling tired. [5 Crewed Mission to Mars Ideas]

On Oct. 19, an EVA day, Jon was awake for 17.5 hours. He took three hours for personal time (reading a book, personal internet, fitness workout); did 2 hours and 25 minutes of food prep and cleanup; 6 EVA-related hours and 2 hours and 25 minutes of EVA support, which includes the writing up of field notes and reports, plus an hour of research, mostly reading and note-taking on inverted channels; 2 hours of meetings (with the whole group and with the small science team); and, finally, 75 minutes of communications to Mission Control.

On his second diary day, Oct. 20, which was a non-EVA day, Jon was awake for 16 hours. He noted down 3 hours and 25 minutes of personal time; 3 hours and 25 minutes research for field science projects; 75 minutes helping with hab engineering; 2 hours of meetings with the whole group and with small groups; 25 minutes in a personal health conversation with me; 5 hours of writing reports to COMMS; and 1 hour seventy five minutes on food prep.

You can tell Jon has spent most of his time in the public service.

If you are still here with me and you are awake, I guess you are wondering how all this activity relates to our health. As a crew, how are we actually doing?

Here at MDRS, we are doing well. To start with, we are all stronger and fitter than when we arrived. Wearing the spacesuit and back packs on EVAs requires physical strength and stamina, and we have been training.

Next, everyone sleeps well; there’s no sound at night. Truthfully, I am the exception to this. Sometimes in my loft at 3 a.m., the moths and I are attracted to free Facebook. And sadly, I have to give up coffee after dinner.

In terms of the food, the crew has few complaints. We would prefer less processed food, for instance, more dried beef or dried fish, fewer sausage crumbles, more dried fruit and nuts, and fewer biscuits — but we are trying hard to cook within the limitations, and our meals are yummy.

Credit: The Mars Society

One day, the greenhouse will be operational, and we’ll grow something in “Martian” soil that we can eat. (Salty Martian soil; does this mean we have to flush out the perchlorate?)

To me, it feels like our crew is the hive.

While we are here, we are safe, our water is good, we eat well, we work hard and we support each other. Living together is part of our work. Because of our shared commitment to Mars and to the mission, we’ve formed an emotional bond that sustains, even if life is not always easy in isolation. For instance, since we arrived here, several of our crewmembers have experienced personal trauma when something has happened at home. When something awful happens (or anytime, really), we are crew family, and we need to comfort each other.

Credit: The Mars Society

We are a science research mission, and the science return is paramount. Cross-training means we are engaged with the science at all levels, from field sampling to laboratory work to science operations. As an international crew with different languages, disciplines, cultural backgrounds and different ways of working, we continue to iron out our misunderstandings to find equilibrium in the working day under pressure. In the hive, we rely on our commander Alex to negotiate equivalences and represent our needs to our Earth-based leaders.

In our small world in the middle of nowhere, we function well because we share goals and maintain a good balance between sleep, nutrition, exercise and work. And the Utah desert keeps us stimulated, as a research environment for all kinds of conditions analogous to Mars. The desert is so ancient and beautiful and otherworldly that sometimes we humans are overwhelmed.

[Source:-Space]