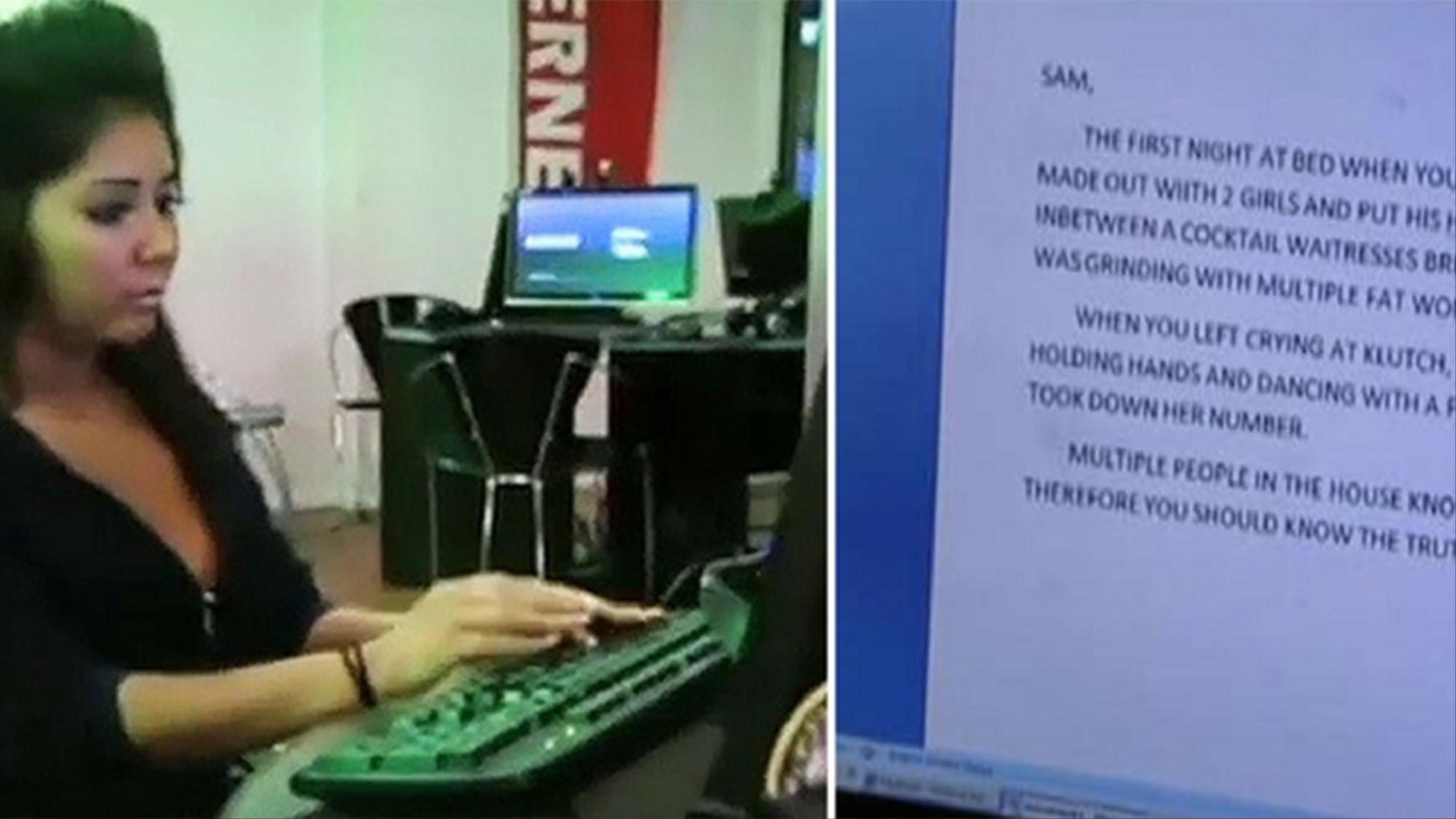

You don’t need to probe too deeply to find evidence of our culture’s inclination towards online oversharing. Take the recent TikTok craze that saw teenage girls dancing to voicemail messages left by their unfaithful or abusive ex-partners. Or the concept of ‘sadfishing’ (that is, seeking sympathy by oversharing online), which earlier this year was considered a sinister enough phenomenon to have caused a minor moral panic amongst parents. Think of people cussing out their exes on their Instagram stories or in viral tweets, or your mum’s friend Carol announcing that she’s had it up to here with “fake people and backstabbers” through the medium of a vengeful, 500-word long Facebook post.

You don’t need to probe too deeply to find evidence of our culture’s inclination towards online oversharing. Take the recent TikTok craze that saw teenage girls dancing to voicemail messages left by their unfaithful or abusive ex-partners. Or the concept of ‘sadfishing’ (that is, seeking sympathy by oversharing online), which earlier this year was considered a sinister enough phenomenon to have caused a minor moral panic amongst parents. Think of people cussing out their exes on their Instagram stories or in viral tweets, or your mum’s friend Carol announcing that she’s had it up to here with “fake people and backstabbers” through the medium of a vengeful, 500-word long Facebook post.

But however endemic the practice may be, it’s still usually thought of as a bad thing. We criticise the people who overshare as narcissists or attention seekers. If we’re talking about our own capacity to overshare, meanwhile, it’s usually with wry self-deprecation; another bad habit to file alongside smoking or eating too much bread. At a time when the discourse around mental health urges us to open up and talk about our feelings, it’s surprisingly rare to see a defence of oversharing. But what does the term actually mean? To accuse someone of oversharing implies there is a correct amount of personal information to share, and a respectable manner in which to go about doing it. But this is obviously subjective — so who decides what’s too much and what metric are they using? Whether deliberately or not, the concept of oversharing can be weaponised in order to stop certain people from speaking about certain topics.

What makes oversharing difficult to define is the fact that it’s so context-dependent. “One of the things I found in my research is that there are different norms for different platforms,” says Dr Ysabel Gerrard, lecturer in Digital Media and Society at the University of Sheffield. “No-one’s going to accuse you of oversharing on Tumblr, for example, because that’s kind of the point — it’s supposed to be like journaling and it’s more likely to be anonymous. You’re far more likely to face this accusation on a platform where you use your real name, which is mostly the case on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.”

Even between these platforms, though, there are different norms of behaviour. It’s become a cliche that while Instagram is about how showing off how enviable your life is, on Twitter there’s reverse clout in posting knowingly about how miserable you are; there’s a particular strain of sardonic humour which involves portraying yourself as a wretched, pathetic, albeit very cultured loser. Certainly I’ve found myself simultaneously posting jokes about my depressive episodes on Twitter, while uploading photos of my brunch and torso to Instagram. This, Dr Gerrard suggests, is not a coincidence. “People have a huge degree of agency or autonomy over how they use platforms but the cultures around them are still really intimately tied to how the spaces were imagined by their founders. By posting in certain ways, we’re often responding to how exactly how these platforms want us to behave.”

Although it’s hard to define oversharing, it’s clear that when an individual is seen to violate norms on a given platform, the consequences can be damaging. Dr Christopher Hand is a lecturer in cyber-pyschology at Glasgow Caledonian University who specialises in online harassment. “What we’ve found,” he says, “is the more people tend to present about themselves, the less sympathy others have when things go wrong. People tend to be judged as bringing about their own negative experiences the more they share them.” This means that spilling the details of your private life online, in a bid to win sympathy, could be misjudged. It also suggests a disturbing callousness on the part of social media users.

It’s not quite so simple, though: Dr Hand’s research also suggests that the more you post on a given platform, purely in terms of volume, the more likely you are to be perceived as socially attractive, outgoing and vivacious. But it matters whether the content you produce is perceived as positive or negative. “That’s where the question of ‘oversharing’ gets really complicated,” Dr Hand says, “because different people perceive what is appropriate very differently.”

Behavioural norms differ across micro-communities within platforms, as well as between different ones. In the online circles I move in, tweeting about sex (often extremely crudely) and mental illness (often to an extreme degree of self-exposure) barely raises an eyebrow. But if I were a politician or a primary school teacher, this probably wouldn’t be the case. But if you do feel as though you’re overstepping the boundaries of whatever online communities you frequent, Dr Hand’s advice is simple. “Consult with people you trust,” he says. “Talk to people you have a strong relationship with in the real world.”