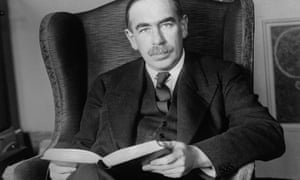

Had you asked John Maynard Keynes what the biggest challenge of the 21st century would be, he wouldn’t have had to think twice.

Leisure. In fact, Keynes anticipated that, barring “disastrous mistakes” by policymakers (austerity during an economic crisis, for instance), the western standard of living would multiply to at least four times that of 1930 within a century. By his calculations, in 2030 we’d be working just 15 hours a week.

In 2000, countries such as the UK and the US were already five times as wealthy as in 1930. Yet as we hurtle through the first decades of the 21st century, our biggest challenges are not too much leisure and boredom, but stress and uncertainty.

What does working less actually solve, I was asked recently. I’d rather turn the question around: is there anything that working less does not solve?

Take climate change. A worldwide shift to a shorter working week could cut the CO2 emitted this century by half. Countries with a shorter working week have asmaller ecological footprint. Consuming less starts with working less – or, better yet – with consuming our prosperity in the form of leisure.

Overtime is deadly. Long working days lead to more errors: tired surgeons are more prone to slip-ups and soldiers who get too little shut-eye are more prone to miss targets. From Chernobyl to the space shuttle Challenger, overworked managers often prove to have played a role in disasters. It is no coincidence that the financial sector, which triggered the biggest disaster of the past decade, is absolutely groaning with people doing overtime.

Countless studies have shown that people who work less are more satisfied with their lives. In a recent poll conducted among working women, German researchers quantified the “perfect day”. The largest share of minutes (106) would go toward “intimate relationships”. Down at the bottom of the list were work (36) and commuting (33). The researchers noted that “in order to maximise wellbeing it is likely that working and consuming (which increases GDP) might play a smaller role in people’s daily activities compared with now”.

Obviously, you can’t simply chop a job up into smaller pieces. Nevertheless, researchers at the International Labour Organization have concluded that job sharing – in which two part-time employees split a workload traditionally assigned to one full-time worker – went a long way towards resolving the last economic crisis. Particularly in times of recession with spiking unemployment and production exceeding demand, sharing jobs can help to soften the blow.

Furthermore, countries with shorter working weeks consistently top gender-equality rankings. The central issue is achieving a more equitable distribution of work. Not until men do their fair share of cooking, cleaning and other domestic labour will women be free to fully participate in the broader economy. Take Sweden, a country with a truly decent system for childcare and paternity leave – and the world’s smallest work-time disparity between men and women.

Besides distributing jobs more equally between the sexes, we also have to share them across the generations. Older people increasingly want to continue working even after hitting pensionable age. But while thirtysomethings are drowning in work, family responsibilities and mortgages, seniors struggle to get hired, even though (some) working has proven health benefits. Young workers who are just entering the labour market may well continue working into their 80s. In return, they could put in not 40 hours a week for all those years, but perhaps just 20-30. “In the 20th century we had a redistribution of wealth,” one leading demographer has observed. “In this century, the great redistribution will be in terms of working hours.”.

And then there is the issue of economic inequality. The countries with the biggest disparities in wealth are precisely those with the longest working weeks. While the poor are working longer hours just to get by, the rich are finding it ever more “expensive” to take time off as their hourly rates rise. Nowadays excessive work and pressure are status symbols. Time to oneself is sooner equated with unemployment and laziness, certainly in countries where the wealth gap has widened.

It doesn’t have to be this way. We have the ability to cut a big chunk off our working week. Not only would it make all of society a whole lot healthier, it would also put an end to untold piles of pointless and even downright harmful tasks (a recent poll found that as many as 37% of British workers think they have a “bullshit job”). A universal basic income would be the best way to give everyone the opportunity to do more unpaid but incredibly important work, such as caring for children and the elderly.

“But wouldn’t everybody just be glued to the TV all the time?”, you may wonder. Actually, it is precisely in overworked countries like Japan, England and the US that people watch an absurd amount of television. Up to four hours a day in England, which adds up to nine years over an average lifetime. Sure, swimming in a sea of spare time won’t be easy. But that’s why a 21st century education should prepare people not only for joining the workforce, but also (and more importantly) for life. “Since men will not be tired in their spare time,” the philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote in 1932, “they will not demand only such amusements as are passive and vapid.”

[SOURCE :-theguardian]